One of the most interesting and charming woody plants in our landscapes is the boxwood. This evergreen shrub has been domesticated by gardeners since the time of the Roman Empire. Pliny wrote about the uses of boxwoods as a garden hedge and as a source of wood for the construction of musical instruments. On a recent chilly morning, I happened to pass a boxwood hedge that looked anything but charming. The usually deep green leaves of the boxwood were mottled yellow and orange and disfigured with bumps and blisters. The plants appeared to have a bad case of the pox. What misfortune had befallen these noble shrubs? After plucking a few leaves from the embattled boxwoods, and carefully removing the lower surface of a leaf, I discovered several tiny, squirming, yellow and orange maggots just beneath the surface. My suspicions were confirmed. These were the larvae of the diabolical boxwood leafminer. The boxwood's blues began last spring in early May when adult boxwood leafminers exited their leafy nursery. On the way out, the adult flies left behind the shed skin of their former pupal case.

With a twist and a turn the female boxwood leafminer drills a hole in the leaf, then lays an egg inside the plant's tissue.

The papery skins, called exuviae, protrude from the bottom surface of the leaf for many days before dropping from the plant. Adult boxwood leafminers are delicate orange flies closely resembling mosquitoes. After mating, the female fly seeks the undersurface of a young leaf. Using a small drill-like structure at the tip of her abdomen, she punches a tiny hole in the surface and lays an egg in the soft tissue beneath. From this egg hatches the tiny yellow larva called the boxwood leafminer. During summer and autumn, as the leafminer grows, the plant produces a small circle of cells around the developing larva. These cells serve as a source of food for the maggot.

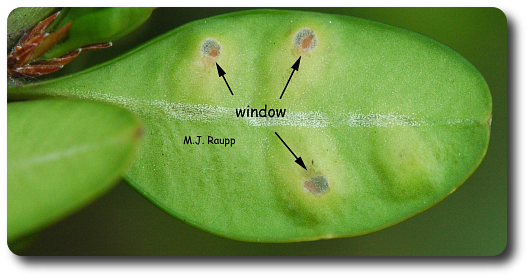

After completing development and to escape from the leaf, leafminer larvae cut windows in the lower surface.

Development slows during the chilly months of winter and early spring, but by April, larvae grow rapidly as the boxwood ramps-up its activity with the return of warmer temperatures. To escape the protected confines of its mine, the leafminer has a clever trick. Just before becoming an adult, the maggot moves to the lower surface of the leaf and carefully removes almost all of the leaf tissue until only a thin layer is left. This layer forms a window used by the pupa as an escape hatch. With a successful exit strategy in place, the larva pupates and, in a few short weeks, the pupa pushes through the window and the adult fly emerges. If you are troubled by boxwood leafminers in your plants, then a good, non-insecticidal solution to reduce this uninvited guest is to plant varieties of boxwoods that are resistant to attack by this insect. A few years ago, we discovered that a variety of boxwood from the highlands of Macedonia was highly resistant to the boxwood leafminer. This variety is called Buxus sempervirens 'Vardar Valley'. You can find it in several nurseries in the area. If you have boxwoods on your property, please visit them in early May and try to catch a glimpse of adult boxwood leafminers as they enter the world of sunshine and wind for a few short days.

References:

A wealth of information on boxwoods can be found in Lynn Batdorf's wonderful "Boxwood Handbook" used as a reference for this story. Information on resistant boxwood varieties came from the article entitled "Integrated approaches for managing the boxwood leafminer, Monoarthropalpus flavus" by Raupp, Mars and d'Eustachio. To learn more about the life and times of the boxwood leafminer, please visit the following websites.

http://www.hgic.umd.edu/_media/documents/hg52_001.pdf

http://www.actahort.org/members/showpdf?booknrarnr=630_6